Baryon

A baryon is a composite particle made up of three quarks (as distinct from mesons, which comprise one quark and one antiquark). Baryons and mesons belong to the hadron family, which are the quark-based particles. The name "baryon" comes from the Greek word for "heavy" (βαρύς, barys), because, at the time of their naming, most known particles had lower masses than the baryons.

As quark-based particles, baryons participate in the strong interaction, whereas leptons, which are not quark-based, do not. The most familiar baryons are the protons and neutrons that make up most of the mass of the visible matter in the universe. Electrons (the other major component of the atom) are leptons. Each baryon has a corresponding antiparticle (antibaryon) where quarks are replaced by their corresponding antiquarks. For example, a proton is made of two up quarks and one down quark; and its corresponding antiparticle, the antiproton, is made of two up antiquarks and one down antiquark.

Until recently, it was believed that some experiments showed the existence of pentaquarks — "exotic" baryons made of four quarks and one antiquark.[1][2] The particle physics community as a whole did not view their existence as likely in 2006,[3] and in 2008, considered evidence to be overwhelmingly against the existence of the reported pentaquarks.[4]

Contents |

Background

Baryons are strongly interacting fermions — that is, they experience the strong nuclear force and are described by Fermi−Dirac statistics, which apply to all particles obeying the Pauli exclusion principle. This is in contrast to the bosons, which do not obey the exclusion principle.

Baryons, along with mesons, are hadrons, meaning they are particles composed of quarks. Quarks have baryon numbers of B = 1⁄3 and antiquarks have baryon number of B = −1⁄3. The term "baryon" usually refers to triquarks - baryons made of three quarks (B = 1⁄3 + 1⁄3 + 1⁄3 = 1). Other exotic baryons have been proposed, such as pentaquarks — baryons made of four quarks and one antiquark (B = 1⁄3 + 1⁄3 + 1⁄3 + 1⁄3 − 1⁄3 = 1), but their existence is not generally accepted. In theory, heptaquarks (5 quarks, 2 antiquarks), nonaquarks (6 quarks, 3 antiquarks), etc. could also exist.

Baryonic matter

Baryonic matter is matter composed mostly of baryons (by mass), which includes atoms of any sort (and thus includes nearly all matter that we may encounter or experience in everyday life, including our bodies). Non-baryonic matter, as implied by the name, is any sort of matter that is not composed primarily of baryons. This might include such ordinary matter as neutrinos or free electrons; however, it may also include exotic species of non-baryonic dark matter, such as supersymmetric particles, axions, or black holes. The distinction between baryonic and non-baryonic matter is important in cosmology, because Big Bang nucleosynthesis models set tight constraints on the amount of baryonic matter present in the early universe.

The very existence of baryons is also a significant issue in cosmology because we have assumed that the Big Bang produced a state with equal amounts of baryons and antibaryons. The process by which baryons come to outnumber their antiparticles is called baryogenesis (in contrast to a process by which leptons account for the predominance of matter over antimatter, leptogenesis).

Baryogenesis

Experiments are consistent with the number of quarks in the universe being a constant and, to be more specific, the number of baryons being a constant; in technical language, the total baryon number appears to be conserved. Within the prevailing Standard Model of particle physics, the number of baryons may change in multiples of three due to the action of sphalerons, although this is rare and has not been observed under experiment. Some grand unified theories of particle physics also predict that a single proton can decay, changing the baryon number by one; however, this has not yet been observed under experiment. The excess of baryons over antibaryons in the present universe is thought to be due to non-conservation of baryon number in the very early universe, though this is not well understood.

Properties

Isospin and charge

The concept of isospin was first proposed by Werner Heisenberg in 1932 to explain the similarities between protons and neutrons under the strong interaction.[5] Although they had different electric charges, their masses were so similar that physicists believed they were actually the same particle. The different electric charges were explained as being the result of some unknown excitation similar to spin. This unknown excitation was later dubbed isospin by Eugene Wigner in 1937.[6]

This belief lasted until Murray Gell-Mann proposed the quark model in 1964 (containing originally only the u, d, and s quarks).[7] The success of the isospin model is now understood to be the result of the similar masses of the u and d quarks. Since the u and d quarks have similar masses, particles made of the same number then also have similar masses. The exact specific u and d quark composition determines the charge, as u quarks carry charge +2⁄3 while d quarks carry charge −1⁄3. For example the four Deltas all have different charges (Δ++

(uuu), Δ+

(uud), Δ0

(udd), Δ−

(ddd)), but have similar masses (~1,232 MeV/c2) as they are each made of a combination of three u and d quarks. Under the isospin model, they were considered to be a single particle in different charged states.

The mathematics of isospin was modeled after that of spin. Isospin projections varied in increments of 1 just like those of spin, and to each projection was associated a "charged state". Since the "Delta particle" had four "charged states", it was said to be of isospin I = 3⁄2. Its "charged states" Δ++

, Δ+

, Δ0

, and Δ−

, corresponded to the isospin projections I3 = +3⁄2, I3 = +1⁄2, I3 = −1⁄2, and I3 = −3⁄2, respectively. Another example is the "nucleon particle". As there were two nucleon "charged states", it was said to be of isospin 1⁄2. The positive nucleon N+

(proton) was identified with I3 = +1⁄2 and the neutral nucleon N0

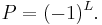

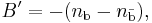

(neutron) with I3 = −1⁄2.[8] It was later noted that the isospin projections were related to the up and down quark content of particles by the relation:

where the n's are the number of up and down quarks and antiquarks.

In the "isospin picture", the four Deltas and the two nucleons were thought to be the different states of two particles. However in the quark model, Deltas are different states of nucleons (the N++ or N− are forbidden by Pauli's exclusion principle). Isospin, although conveying an inaccurate picture of things, is still used to classify baryons, leading to unnatural and often confusing nomenclature.

Flavour quantum numbers

The strangeness flavour quantum number S (not to be confused with spin) was noticed to go up and down along with particle mass. The higher the mass, the lower the strangeness (the more s quarks). Particles could be described with isospin projections (related to charge) and strangeness (mass) (see the uds octet and decuplet figures on the right). As other quarks were discovered, new quantum numbers were made to have similar description of udc and udb octets and decuplets. Since only the u and d mass are similar, this description of particle mass and charge in terms of isospin and flavour quantum numbers works well only for octet and decuplet made of one u, one d, and one other quark, and breaks down for the other octets and decuplets (for example, ucb octet and decuplet). If the quarks all had the same mass, their behaviour would be called symmetric, as they would all behave in exactly the same way with respect to the strong interaction. Since quarks do not have the same mass, they do not interact in the same way (exactly like an electron placed in an electric field will accelerate more than a proton placed in the same field because of its lighter mass), and the symmetry is said to be broken.

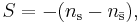

It was noted that charge (Q) was related to the isospin projection (I3), the baryon number (B) and flavour quantum numbers (S, C, B′, T) by the Gell-Mann–Nishijima formula:[8]

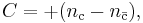

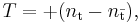

where S, C, B′, and T represent the strangeness, charm, bottomness and topness flavour quantum numbers, respectively. They are related to the number of strange, charm, bottom, and top quarks and antiquark according to the relations:

meaning that the Gell-Mann–Nishijima formula is equivalent to the expression of charge in terms of quark content:

Spin, orbital angular momentum, and total angular momentum

Spin (quantum number S) is a vector quantity that represents the "intrinsic" angular momentum of a particle. It comes in increments of 1⁄2 ħ (pronounced "h-bar"). The ħ is often dropped because it is the "fundamental" unit of spin, and it is implied that "spin 1" means "spin 1 ħ". In some systems of natural units, ħ is chosen to be 1, and therefore does not appear anywhere.

Quarks are fermionic particles of spin 1⁄2 (S = 1⁄2). Because spin projections varies in increments of 1 (that is 1 ħ), a single quark has a spin vector of length 1⁄2, and has two spin projections (Sz = +1⁄2 and Sz = −1⁄2). Two quarks can have their spins aligned, in which case the two spin vectors add to make a vector of length S = 1 and three spin projections (Sz = +1, Sz = 0, and Sz = −1). If two quarks have unaligned spins, the spin vectors add up to make a vector of length S = 0 and has only one spin projection (Sz = 0), etc. Since baryons are made of three quarks, their spin vectors can add to make a vector of length S = 3⁄2, which has four spin projections (Sz = +3⁄2, Sz = +1⁄2, Sz = −1⁄2, and Sz = −3⁄2), or a vector of length S = 1⁄2 with two spin projections (Sz = +1⁄2, and Sz = −1⁄2).[9]

There is another quantity of angular momentum, called the orbital angular momentum (quantum number L), that comes in increments of 1 ħ, which represent the angular moment due to quarks orbiting around each other. The total angular momentum (quantum number J) of a particle is therefore the combination of intrinsic angular momentum (spin) and orbital angular momentum. It can take any value from J = |L − S| to J = |L + S|, in increments of 1.

| Spin (S) | Orbital angular momentum (L) | Total angular momentum (J) | Parity (P) (See below) |

Condensed notation (JP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1⁄2 | 0 | 1⁄2 | + | 1⁄2+ |

| 1 | 3⁄2, 1⁄2 | − | 3⁄2−, 1⁄2− | |

| 2 | 5⁄2, 3⁄2 | + | 5⁄2+, 3⁄2+ | |

| 3 | 7⁄2, 5⁄2 | − | 7⁄2−, 5⁄2− | |

| 3⁄2 | 0 | 3⁄2 | + | 3⁄2+ |

| 1 | 5⁄2, 3⁄2, 1⁄2 | − | 5⁄2−, 3⁄2−, 1⁄2− | |

| 2 | 7⁄2, 5⁄2, 3⁄2, 1⁄2 | + | 7⁄2+, 5⁄2+, 3⁄2+, 1⁄2+ | |

| 3 | 9⁄2, 7⁄2, 5⁄2, 3⁄2 | − | 9⁄2−, 7⁄2−, 5⁄2−, 3⁄2− |

Particle physicists are most interested in baryons with no orbital angular momentum (L = 0), as they correspond to ground states—states of minimal energy. Therefore the two groups of baryons most studied are the S = 1⁄2; L = 0 and S = 3⁄2; L = 0, which corresponds to J = 1⁄2+ and J = 3⁄2+, respectively, although they are not the only ones. It is also possible to obtain J = 3⁄2+ particles from S = 1⁄2 and L = 2, as well as S = 3⁄2 and L = 2. This phenomenon of having multiple particles in the same total angular momentum configuration is called degeneracy. How to distinguish between these degenerate baryons is an active area of research in baryon spectroscopy.[10][11]

Parity

If the universe were reflected in a mirror, most of the laws of physics would be identical — things would behave the same way regardless of what we call "left" and what we call "right". This concept of mirror reflection is called intrinsic parity or parity (P). Gravity, the electromagnetic force, and the strong interaction all behave in the same way regardless of whether or not the universe is reflected in a mirror, and thus are said to conserve parity (P-symmetry). However, the weak interaction does distinguish "left" from "right", a phenomenon called parity violation (P-violation).

Based on this, one might think that, if the wavefunction for each particle (in more precise terms, the quantum field for each particle type) were simultaneously mirror-reversed, then the new set of wavefunctions would perfectly satisfy the laws of physics (apart from the weak interaction). It turns out that this is not quite true: In order for the equations to be satisfied, the wavefunctions of certain types of particles have to be multiplied by −1, in addition to being mirror-reversed. Such particle types are said to have negative or odd parity (P = −1, or alternatively P = –), while the other particles are said to have positive or even parity (P = +1, or alternatively P = +).

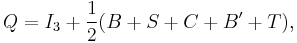

For baryons, the parity is related to the orbital angular momentum by the relation:[12]

As a consequence, baryons with no orbital angular momentum (L = 0) all have even parity (P = +).

Nomenclature

Baryons are classified into groups according to their isospin (I) values and quark (q) content. There are six groups of baryons—nucleon (N), Delta (Δ), Lambda (Λ), Sigma (Σ), Xi (Ξ), and Omega (Ω). The rules for classification are defined by the Particle Data Group. These rules consider the up (u), down (d) and strange (s) quarks to be light and the charm (c), bottom quark (b), and top (t) to be heavy. The rules cover all the particles that can be made from three of each of the six quarks, even though baryons made of t quarks are not expected to exist because of the t quark's short lifetime. The rules do not cover pentaquarks.[13]

- Baryons with three u and/or d quarks are N's (I = 1⁄2) or Δ's (I = 3⁄2).

- Baryons with two u and/or d quarks are Λ's (I = 0) or Σ's (I = 1). If the third quark is heavy, its identity is given by a subscript.

- Baryons with one u or d quark are Ξ's (I = 1⁄2). One or two subscripts are used if one or both of the remaining quarks are heavy.

- Baryons with no u or d quarks are Ω's (I = 0), and subscripts indicate any heavy quark content.

- Baryons that decay strongly have their masses as part of their names. For example, Σ0 does not decay strongly, but Δ++(1232) does.

It is also a widespread (but not universal) practice to follow some additional rules when distinguishing between some states that would otherwise have the same symbol.[8]

- Baryons in total angular momentum J = 3⁄2 configuration that have the same symbols as their J = 1⁄2 counterparts are denoted by an asterisk ( * ).

- Two baryons can be made of three different quarks in J = 1⁄2 configuration. In this case, a prime ( ′ ) is used to distinguish between them.

-

- Exception: When two of the three quarks are one up and one down quark, one baryon is dubbed Λ while the other is dubbed Σ.

Quarks carry charge, so knowing the charge of a particle indirectly gives the quark content. For example, the rules above say that a Λ+

c contains a c quark and some combination of two u and/or d quarks. The c quark as a charge of (Q = +2⁄3), therefore the other two must be a u quark (Q = +2⁄3), and a d quark (Q = −1⁄3) to have the correct total charge (Q = +1).

See also

| Book: Hadronic Matter

Book: Particles of the Standard Model |

|

| Wikipedia books are collections of articles that can be downloaded or ordered in print. | |

Notes

- ^ H. Muir (2003)

- ^ K. Carter (2003)

- ^ W.-M. Yao et al. (2006): Particle listings – Θ+

- ^ C. Amsler et al. (2008): Pentaquarks

- ^ W. Heisenberg (1932)

- ^ E. Wigner (1937)

- ^ M. Gell-Mann (1964)

- ^ a b c S.S.M. Wong (1998a)

- ^ R. Shankar (1994)

- ^ H. Garcilazo et al. (2007)

- ^ D.M. Manley (2005)

- ^ S.S.M. Wong (1998b)

- ^ C. Amsler et al. (2008): Naming scheme for hadrons

References

- C. Amsler et al. (Particle Data Group) (2008). "Review of Particle Physics". Physics Letters B 667 (1): 1–1340. Bibcode 2008PhLB..667....1P. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.07.018.

- H. Garcilazo, J. Vijande, and A. Valcarce (2007). "Faddeev study of heavy-baryon spectroscopy". Journal of Physics G 34 (5): 961–976. doi:10.1088/0954-3899/34/5/014.

- K. Carter (2006). "The rise and fall of the pentaquark". Fermilab and SLAC. http://www.symmetrymagazine.org/cms/?pid=1000377. Retrieved 2008-05-27.

- W.-M. Yao et al.(Particle Data Group) (2006). "Review of Particle Physics". Journal of Physics G 33: 1–1232. arXiv:astro-ph/0601168. Bibcode 2006JPhG...33....1Y. doi:10.1088/0954-3899/33/1/001.

- D.M. Manley (2005). "Status of baryon spectroscopy". Journal of Physics: Conference Series 5: 230–237. Bibcode 2005JPhCS...9..230M. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/9/1/043.

- H. Muir (2003). "Pentaquark discovery confounds sceptics". New Scientist. http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn3903. Retrieved 2008-05-27.

- S.S.M. Wong (1998a). "Chapter 2—Nucleon Structure". Introductory Nuclear Physics (2nd ed.). New York (NY): John Wiley & Sons. pp. 21–56. ISBN 0-471-23973-9.

- S.S.M. Wong (1998b). "Chapter 3—The Deuteron". Introductory Nuclear Physics (2nd ed.). New York (NY): John Wiley & Sons. pp. 57–104. ISBN 0-471-23973-9.

- R. Shankar (1994). Principles of Quantum Mechanics (2nd ed.). New York (NY): Plenum Press. ISBN 0-306-44790-8.

- E. Wigner (1937). "On the Consequences of the Symmetry of the Nuclear Hamiltonian on the Spectroscopy of Nuclei". Physical Review 51 (2): 106–119. Bibcode 1937PhRv...51..106W. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.51.106.

- M. Gell-Mann (1964). "A Schematic of Baryons and Mesons". Physics Letters 8 (3): 214–215. Bibcode 1964PhL.....8..214G. doi:10.1016/S0031-9163(64)92001-3.

- W. Heisenberg (1932). "Über den Bau der Atomkerne I". Zeitschrift für Physik 77: 1–11. Bibcode 1932ZPhy...77....1H. doi:10.1007/BF01342433. (German)

- W. Heisenberg (1932). "Über den Bau der Atomkerne II". Zeitschrift für Physik 78: 156–164. Bibcode 1932ZPhy...78..156H. doi:10.1007/BF01337585. (German)

- W. Heisenberg (1932). "Über den Bau der Atomkerne III". Zeitschrift für Physik 80: 587–596. Bibcode 1933ZPhy...80..587H. doi:10.1007/BF01335696. (German)

External links

- Particle Data Group—Review of Particle Physics (2008).

- Georgia State University—HyperPhysics

- Baryons made thinkable, an interactive visualisation allowing physical properties to be compared

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![I_\mathrm{3}=\frac{1}{2}[(n_\mathrm{u}-n_\mathrm{\bar{u}})-(n_\mathrm{d}-n_\mathrm{\bar{d}})],](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/412e99fd108f559422f28c97a14c6455.png)

![Q=\frac{2}{3}[(n_\mathrm{u}-n_\mathrm{\bar{u}})%2B(n_\mathrm{c}-n_\mathrm{\bar{c}})%2B(n_\mathrm{t}-n_\mathrm{\bar{t}})]-\frac{1}{3}[(n_\mathrm{d}-n_\mathrm{\bar{d}})%2B(n_\mathrm{s}-n_\mathrm{\bar{s}})%2B(n_\mathrm{b}-n_\mathrm{\bar{b}})].](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/bd310e54f52210646abe9e4d08680a7a.png)